Granulate or Shred: Which Makes Sense for You?

That is the size-reduction question confronting many processors today. Look here for some guidance.

Granulation, grinding, chopping, and shredding are all common terms to describe the task of size reduction of scrap that is a byproduct of plastic processing. Every plastics processing facility generates both startup waste and a certain level of imperfect product that is rejected as scrap.

For many processors, successfully reclaiming their scrap can make the difference between profit and loss. However, in order to retain its value—whether it is recycled back into the process or sold to others for recycling—scrap usually must be reduced to a manageable and uniform size. That’s where granulation and shredding equipment comes in.

Granulators are a common sight in plastics processing plants and they can be classified generally into two groups. Beside-the-machine models are usually used to grind relatively small volumes of sprues, runners, off-spec parts, and edge trim from film lines for immediate recycling back into the process. Central granulators, as their name implies, are often located in a room separate from the production floor. They are usually bigger and more powerful and are used to chop large volumes of scrap, often from multiple processing lines or molding cells.

They may be fitted with special feeding hoppers to accommodate long parts like pipe or profile extrusions or wide materials like sheet, or to unwind and granulate off-spec and startup film rolls.

Heavy-duty “hog” granulators are used to handle large, heavy parts and purgings. Generally, granulators operate at high speeds with relatively low torque. Even so-called “low-speed” granulators have rotors that turn at upwards of 190 rpm and standard-speed granulators operate at 400 to 500 rpm or more.

Shredders, on the other hand, tend to operate at lower speeds (100 to 130 rpm) with high torque that allows them to chew through almost anything. This explains why shredders are so common in recycling applications involving wood, metal, and paper, and why they are increasingly popular in plastics recycling. These machines can be provided in single-shaft designs that cut down against one or more stationary bed knives, or dual-shaft models that employ two counter-rotating shafts that cut against each other to shred scrap.

Dual-shaft models are thought to be more efficient in shredding bulky scrap but are more complex and more prone to shaft damage. In addition, knife maintenance is doubled in dual-shaft models. Single-shaft models typically provide a larger, more robust rotor and utilize stationary bed knives, thus simplifying service and offering heavier duty operation. Single-shaft shredders are generally regarded as more productive on rigid plastics as well as film and fiber materials, and these are the units that are rapidly gaining popularity in the plastics industry.

If you listed all the different kinds of scrap that might be generated in a plastics processing plant—bottles, sprues, runners, small and large molded parts, film, sheet, pipe, fibers, purgings, profiles, etc.—any of it could be processed equally well by either a granulator or a shredder. So, how do you determine which of the two size-reduction technologies is best?

Four main factors will likely enter into the decision:

•Scrap volume;

•Density;

•Feeding method;

•Required final condition.

HOW MUCH SCRAP WILL BE PROCESSED?

There really is no minimum throughput rate for a granulator. Except for the energy required to start and run the rotor, a properly sized granulator can chop thousands of pounds of scrap as easily as a few pounds. Small, beside-the-machine granulators are specifically designed for handling a steady stream of scrap at rates up to about 1000 lb/hr (454 kg/hr). Larger, central units can be installed to handle upwards of 9000 lb/hr (4100 kg/hr) under either meter-feed or batch-feed conditions.

The only real limitation is the size and configuration of the feed opening and cutting chamber, and the need to avoid over-feeding and jamming the rotor. To prevent jamming, granulator manufacturers typically configure their machines to take smaller bites of the scrap and use heavy flywheels and high-horsepower drive motors to power through thick sections, but rotor damage and jamming are always a potential issue.

Shredders, on the other hand, don’t normally work efficiently (and sometimes won’t work at all) at extremely low throughputs. This is especially true of single-shaft shredders, which use a horizontal hydraulic ram to drive scrap material into the cutting area at the intersection of the rotor and the stationary knives. The more scrap there is in the feed bin and the heavier it is, the easier it is for the ram to push it forward into the rotor.

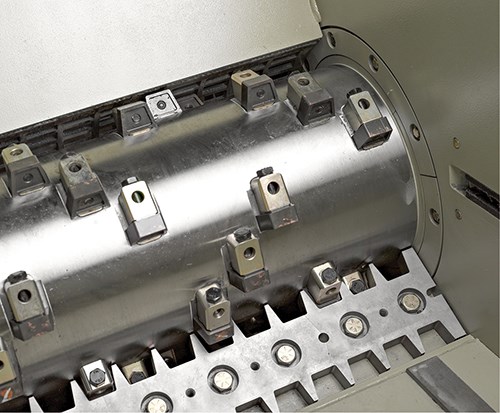

Shredder rotors are usually solid steel (or heavy-duty weldments) with rugged saw-tooth cutters that intermesh with the stationary knives to shred the scrap. The forward pressure of the feed ram and the rotor drive are continually monitored and controlled so that the ram’s feed rate is optimized for aggressive shredding without overloading. Most models include controls that can quickly reverse the rotor to clear jams that can occur from overly aggressive feeding, particularly of thick scrap, or foreign matter like tramp metal.

So, while granulators can handle high volumes of scrap, it is probably worthwhile to consider whether a shredder might be an equally effective solution.

WHAT IS THE SCRAP DENSITY?

Some scrap can put a considerable strain on size-reduction equipment. Purgings, which can be several inches thick and weigh 30 or 40 lb, are a good example. Tossing one into a granulator, even a central granulator with a hog rotor and plenty of horsepower, can create a lot of noise, cause power spikes, and potentially damage the granulator. To avoid these problems, companies who frequently have purgings to recycle will first cut them into smaller pieces using a band saw or a similar tool. For a shredder, on the other hand, purgings are no problem. In fact, a whole bin full of them can be dumped in the open hopper and the machine will devour them quite efficiently.

The same holds true for a dense bale of crushed laundry-detergent bottles. However, in undensified form loose bottles can bounce around in a shredder so that cutting efficiency goes way down. Those same lightweight bottles would pose no problem, however, if they were conveyor-fed to the tangential cutting chamber of a granulator.

Off-spec rolls of plastic film and fiber, some weighing hundreds of pounds each, are another example of scrap that is ideal for shredding. The entire roll can be dropped into a shredder while, to process the same scrap through a granulator, the roll stock would need to be cut into slabs or unwound before it could be granulated. Special cutters are available for these shredder applications to ensure that long strips of film and fiber strands do not wrap themselves around the rotor.

If you need to process high-volumes of heavy, dense scrap—whether purgings or thick-walled pipe or sheet—and you want to avoid labor-intensive prep work before granulation, you might think about using a shredder.

WHAT FEEDING METHOD IS NEEDED?

As the preceding discussion about scrap volume and density suggests, shredders require only the very simplest feeding systems. In fact, shredders work best when heavy, dense scrap is simply dumped into the feed hopper. A hydraulic ram travels laterally in a channel built into the bottom of the hopper and pushes material into the rotor. When the ram is retracted, the weight of the scrap in the top of the hopper tends to force it down into the feed channel where it can be again pressed forward by the ram. This makes a shredder a “dump-and-forget” machine.

Most granulators, on the other hand, are exactly the opposite. As noted, flooding the cutting chamber with scrap can cause power spikes and even jam the rotor. Most granulators must be meter-fed by hand, robot, conveyor, or some other special feeding mechanism. So, processing scrap through a shredder may involve less labor than a granulator would.

WHAT’S THE FINAL MATERIAL CONDITION?

Probably the single biggest difference between a granulator and a shredder is the form of the scrap after size reduction. A shredder is a single-stage device that chops scrap into small, more manageable pieces. The size of those pieces is partly determined by the size of the holes in the classifying screens, which can range from as large as 2 in. (50.8 mm) diam. to less than half that size. That means the shredded product is likely to be considerably larger than virgin plastic pellets, and there will probably be a wide variation in particle size and shape and a lot of dust and fines as well.

This may not be a problem if the material is going to be shipped off to a recycler for resale and or reprocessing. However, if the material is going to be returned to the molding machine or extruder in a blend with virgin pellets, shredded scrap may need to go through a secondary granulation process in order to develop optimal size and uniformity. Ground scrap, which is similar in size to virgin material, flows more easily and mixes better with virgin resin and additives in the processing machine.

A well-designed granulator, kept in good mechanical condition with sharp blades, is the best tool available to produce consistently uniform granulate. In operation, rotor knives make their initial cuts into the scrap and then continue their rotation to cut along the inner surface of the sizing screen, further reducing the size of the scrap until it passes through the screen holes and out of the granulator’s cutting chamber. Holes are usually 0.25 to 0.375 in. (6.35 to 9.5 mm) diam., so the particles passing through tend to be granular and close to the size of virgin pellets.

NOT ALWAYS EITHER/OR

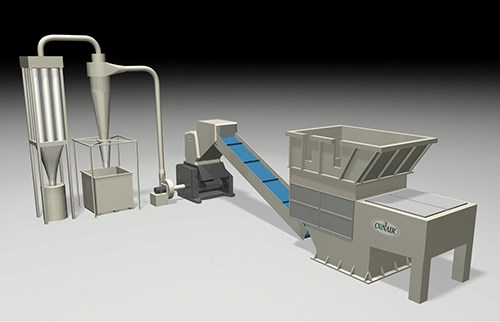

Just because granulators and shredders operate differently, and each has different advantages, does not mean processors must choose one or the other. In fact, shredders often perform the coarse size-reduction task, while the scrap is subsequently channeled into a granulator for final sizing to yield a consistent, uniform feed material. The shredder does what it is best at—efficiently cutting large volumes of heavy plastic scrap into smaller, more manageable pieces with a minimum of operator involvement. Then, the granulator can do its thing, handling less demanding grinding tasks and, when necessary, turning shredded scrap into valuable, process-ready regrind.

If you look closely at the kind of scrap generated by your process, and think about how it will be handled after size reduction, it should become clear very quickly whether you need the brute force of a shredder or the finesse of a granulator. A supplier that can offer you both options will be able to help you analyze your situation and make the best decision for your needs.

Related Content

Brueckner Group USA Moving to Bigger Space

New facility in New Hampshire will serve the local customer base better and enhance capabilities in the North American market.

Read MoreUS Merchants Makes its Mark in Injection Molding

In less than a decade in injection molding, US Merchants has acquired hundreds of machines spread across facilities in California, Texas, Virginia and Arizona, with even more growth coming.

Read MoreOMV Technologies Gets New CEO

Kooper brings 33 years of experience in the industrial and consumer packaging industries to OMV--the closed-loop, turnkey, inline extrusion, thermoforming and tooling systems manufacturer.

Read MoreCobot Creates 'Cell Manufacturing Dream' for Thermoformer

Kal Plastics deploys Universal Robot trimming cobot for a fraction of the cost and lead time of a CNC machine, cuts trimming time nearly in half and reduces late shipments to under 1% — all while improving employee safety and growth opportunities.

Read MoreRead Next

How Polymer Melts in Single-Screw Extruders

Understanding how polymer melts in a single-screw extruder could help you optimize your screw design to eliminate defect-causing solid polymer fragments.

Read MoreLead the Conversation, Change the Conversation

Coverage of single-use plastics can be both misleading and demoralizing. Here are 10 tips for changing the perception of the plastics industry at your company and in your community.

Read More

.png;maxWidth=300;quality=90)