The Importance of Barrel Heat and Melt Temperature

Barrel temperature may impact melting in the case of very small extruders running very slowly. Otherwise, melting is mainly the result of shear heating of the polymer.

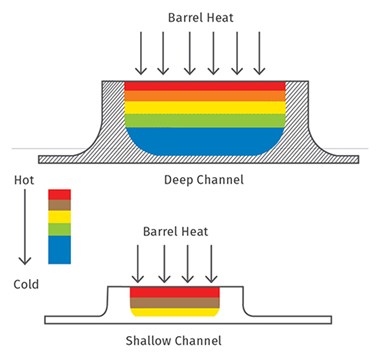

As shown here, the deeper the screw channels, the much less impact that barrel heat will have on melting the polymer.

It’s generally assumed that much of the heat for melting is generated by the barrel. That’s true in some instances, but the heat from the barrel has to be conducted from the barrel wall clear through the layer of polymer in the screw channel to do any significant melting. Since polymers are excellent insulators, conducting heat is one of their worst features.

In reality, melting occurs in single-screw extruders primarily as a result of shear heating of the polymer. Shear heating is the result of a polymer-filled screw rotating within the barrel. This is a lot easier to understand if you picture the screw as a simple round shaft with no flights turning inside a heated tube filled with a highly viscous material. The amount of shear heating versus the degree of heat conducted from the barrel for melting depends a lot on the gap between the shaft and tube. Generally speaking, the larger the screw, the deeper the channels, and the more important the contribution of shear heating.

In the case of smaller screws with shallower channel depths, the transfer of heat into the solid occurs more quickly because there is less distance for the heat to travel through the insulating layer of the polymer itself. In these cases, the transient conductive heating of the solid polymer from the barrel heat can add significantly to the melting or softening temperature suitable for extrusion processing. But that’s only if there is enough time available.

Except in cases where the screw is very small and turning very slowly, depending on conductive melting severely limits the potential output by waiting for the heat to fully penetrate the solid polymer. The interval of time to conduct full heat transfer increases exponentially with thickness, so that the difference in time to transfer heat through even a small increase in polymer thickness can be surprising.

Do you grill? If you cook a thick steak for a half-hour, you might wind up charring the outside while the inside stays raw due to poor heat transfer. Meanwhile, a thinner hamburger patty will cook completely through in a few minutes.

Screw Design

As screws get larger and the channel depths increase, the effect of barrel heat becomes very minor due to the limitation on transferring conducted heat into the thicker solid mass in a reasonable amount of time. With larger screws, almost all of the energy for melting (and temperature rise after melting) emanates from the drive energy through viscous dissipation or shearing of the polymer.

This makes design of the melting portion of larger screws progressively more important and exacting. I’ve conducted many “push-outs” of 12-in. screws full of polymer; patterns revealed that even after several hours of heating, the melting had only slightly penetrated into the full polymer depth.

Conversely, with push-outs of 2-in. screws after 30 min, it was hard to determine some of the melting pattern, with the exception of several flights after the feed opening. Transient heating calculations for one-dimensional transfer shows that a doubling of the polymer thickness typically quadruples the time to transfer heat.

Conductive heating has a number of effects on processing. Small screws turning slowly use less drive power per pound of output than do larger screws because conductive heating plays a larger role. It’s largely true that a “general-purpose” design for screws under 1.5 in. can run almost any polymer just by adjusting the barrel heating. However, melt uniformity is decreased with high levels of conductive heating because of the varying levels of shear experienced by some portions melting earlier and others later. Mixing is reduced because the shear normally present in melting is largely absent. Stability is usually reduced because of erratic melting rate compared with shear melting.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR: FRANKLAND

Jim Frankland is a mechanical engineer who has been involved in all types of extrusion processing for more than 40 years. He is now president of Frankland Plastics Consulting, LLC. Contact

jim.frankland@comcast.net or (724) 651-9196.

Related Content

A Simpler Way to Calculate Shot Size vs. Barrel Capacity

Let’s take another look at this seemingly dull but oh-so-crucial topic.

Read MoreSolve Four Common Problems in PET Stretch-Blow Molding

Here’s a quick guide to fixing four nettlesome problems in processing PET bottles.

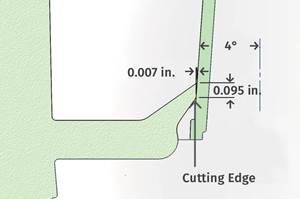

Read MoreTunnel Gates for Mold Designers, Part 1

Of all the gate types, tunnel gates are the most misunderstood. Here’s what you need to know to choose the best design for your application.

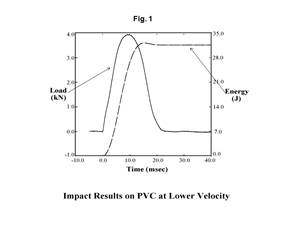

Read MoreThe Strain Rate Effect

The rate of loading for a plastic material is a key component of how we perceive its performance.

Read MoreRead Next

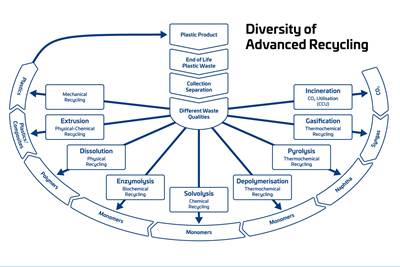

Advanced Recycling: Beyond Pyrolysis

Consumer-product brand owners increasingly see advanced chemical recycling as a necessary complement to mechanical recycling if they are to meet ambitious goals for a circular economy in the next decade. Dozens of technology providers are developing new technologies to overcome the limitations of existing pyrolysis methods and to commercialize various alternative approaches to chemical recycling of plastics.

Read MoreLead the Conversation, Change the Conversation

Coverage of single-use plastics can be both misleading and demoralizing. Here are 10 tips for changing the perception of the plastics industry at your company and in your community.

Read MoreHow Polymer Melts in Single-Screw Extruders

Understanding how polymer melts in a single-screw extruder could help you optimize your screw design to eliminate defect-causing solid polymer fragments.

Read More.jpg;width=70;height=70;mode=crop)