EXTRUSION: Melting 101

Learn the basics on how polymer melts in a single screw. Barrel temperature plays less of a role than you might think.

Surprising as it might seem, plastics processors generally don’t understand how polymer melts in a single-screw extruder. Even those with a great deal of practical experience have problems grasping the concept, and it’s an important one to understand to maximize the efficiencies of your extrusion operation.

To simplify the concept and illustrate the basic mechanism, think of the barrel rotating around a stationary screw. Most single-screw analysis is based this technique, and I’ve found that it simplifies the geometry and provides the same results.

The polymer enters the screw as particles (pellets, powder, flakes) and is compacted by the screw flights into a tightly compacted mass (see A in the accompanying illustration). At that point, friction between the pellets and the barrel raises the temperature of the polymer closest to the barrel wall. In addition, some heat is conducted into the polymer from the hot barrel, helping to form a thin film of melt between the barrel and solid polymer (see B in the accompanying illustration).

From that point forward the energy for melting is developed in the film largely through viscous dissipation or shear heating. Most processors understand the concept of transferred heat from the hot barrel, but viscous dissipation is not as easily grasped, which is unfortunate, since it supplies almost all the energy for polymer melting. What happens as a result is a misguided reliance on barrel temperatures for melting.

So let’s explain viscous dissipation. Viscous dissipation occurs when the melt film sticks to the barrel and to the polymer below. As the barrel turns around the screw, the melted polymer sticking above and below the melt is being continuously stretched like a rubber band. Stretching the melt requires a mechanical force (or torque) to rotate the barrel around the screw. This torque becomes heat in the melt, just as a rubber band or a copper wire becomes warm when rapidly flexed. The energy used for your arm motion is transferred to the rubber band or wire as heat following the law of energy conservation. In the concept discussed here, electrical power to the drive is first converted to mechanical power with the rotation of the barrel, and then the barrel rotation is converted to heat in the film by continuously stretching it between the two surfaces.

During extrusion, this continued stretching introduces more and more heat into the melt. This raises its temperature, and the amount of melt grows as a result of conduction of heat from the film into the solid polymer beneath it. Note that this does not describe the entire melting mechanism, because the flights and compression in a typical screw significantly affect the melting rate.

To be sure, ignoring the effects of the helical flights overly simplifies the melting mechanism but helps to clarify viscous dissipation, which is the main energy source for melting and temperature rise in the melt after melting is completed. Even in the full melting model the rate of melting and temperature rise for a given polymer is similarly proportional to the torque required to rotate the barrel in relation to the screw, and that in turn is equal to the resistance (viscosity) of the film to being stretched.

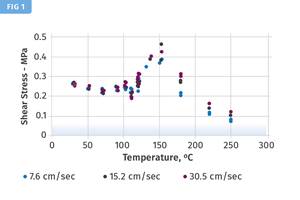

The melting rate is also strongly proportional to the barrel velocity (screw speed) or the rate at which the melt is being stretched. Since torque multiplied by screw speed equal horsepower (Torque=[HP x 63025]/rpm )—and horsepower is the measure of work—this quantifies the torque as being closely proportional to the change in polymer temperature as it traverses the length of the screw. This provides a very simplified explanation of the effects of viscous dissipation. Quantifying this model with a flighted screw is much more complicated, but the melting principle remains the same.

Melting rate—and even the polymer temperature rise after melting for a given screw design and polymer—is largely determined by viscous dissipation, which depends on screw velocity and polymer viscosity for a given polymer. This explains why melt temperature is very much affected by output if screw speed is held constant. Since the torque required to rotate the barrel relative to the screw is heavily dependent on the resistance of the polymer to being stretched and not the mass flow, more flow provides a lower melt temperature and lower flow yields a hotter melt. Barrel heating has a much lesser effect, except in very small extruders.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Jim Frankland is a mechanical engineer who has been involved in all types of extrusion processing for more than 40 years. He is now president of Frankland Plastics Consulting, LLC. Contact jim.frankland@comcast.net or (724)651-9196.

Related Content

How Polymer Melts in Single-Screw Extruders

Understanding how polymer melts in a single-screw extruder could help you optimize your screw design to eliminate defect-causing solid polymer fragments.

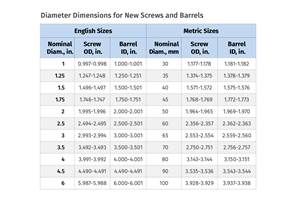

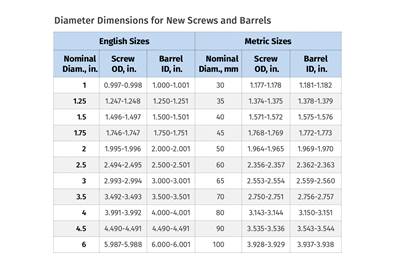

Read MoreTroubleshooting Screw and Barrel Wear in Extrusion

Extruder screws and barrels will wear over time. If you are seeing a reduction in specific rate and higher discharge temperatures, wear is the likely culprit.

Read MoreOptimizing Barrel Temperatures for Single-Screw Extruders

If barrel temperatures are set correctly and screw design is optimized, the extruder will be operating at peak performance, providing maximum profitability. If not, bad things can happen impacting quality and profitability.

Read MoreCooling the Feed Throat and Screw: How Much Water Do You Need?

It’s one of the biggest quandaries in extrusion, as there is little or nothing published to give operators some guidance. So let’s try to shed some light on this trial-and-error process.

Read MoreRead Next

Troubleshooting Screw and Barrel Wear in Extrusion

Extruder screws and barrels will wear over time. If you are seeing a reduction in specific rate and higher discharge temperatures, wear is the likely culprit.

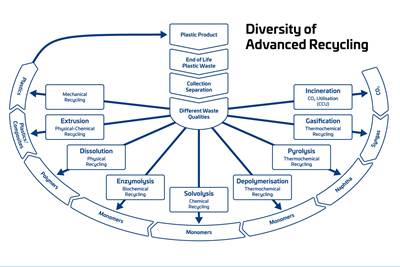

Read MoreAdvanced Recycling: Beyond Pyrolysis

Consumer-product brand owners increasingly see advanced chemical recycling as a necessary complement to mechanical recycling if they are to meet ambitious goals for a circular economy in the next decade. Dozens of technology providers are developing new technologies to overcome the limitations of existing pyrolysis methods and to commercialize various alternative approaches to chemical recycling of plastics.

Read MorePeople 4.0 – How to Get Buy-In from Your Staff for Industry 4.0 Systems

Implementing a production monitoring system as the foundation of a ‘smart factory’ is about integrating people with new technology as much as it is about integrating machines and computers. Here are tips from a company that has gone through the process.

Read More.jpg;width=70;height=70;mode=crop)