Take a Scientific Approach to Troubleshooting

injection Molding Know How

Taking a scientific approach minimizes the 'art' of molding, which is particularly helpful when troubleshooting

Many consider injection molding to be an art form. While certain aspects of molding do remain somewhat mysterious, I believe that taking a scientific approach minimizes the “art” of our craft, which is particularly helpful when troubleshooting. My attempt here is be to establish a first step in troubleshooting the following part or processing problems:

•Non-return valve issues,

•Flash,

•Shorts,

•Weld lines,

•Blushing, or other surface-finish problems,

•Splay,

•Sink,

•Dimensional variation,

•Bubbles, voids,

•Burn marks,

•”Record tracks,”

•Sticking in cavity, core, or sprue,

•”Pin push” or ejector marks,

•Cracking, crazing,

•Machine switchover response.

This is a fairly long list of issues, and with all of them you can get a significant amount of information to start a scientific approach toward a resolution by turning off the second-stage or pack-and-hold pressure. It just might be worth your time to try it. What have you got to lose?

For this first step to be of value it has to be done correctly. There are three methods commonly used for taking off second-stage or pack/hold pressure. You can take hold pressure off by either taking the time off the timer, reducing the hold-pressure setpoint to near zero, or doing both. It seems like you should get the same results with each of these approaches; but due to machine response and other factors, you will not get the same result with each method. Check it out.

On a tool that you are sure will eject the part if you make a short shot, do one trial with taking the hold time off, another leaving the time on and taking hold pressure down to near zero, and a third trial where you reduce both hold time to zero and hold pressure to near zero. You should see a different in the size of the parts. All three should be visibly short by volume (not by weight). If they are not all short it almost surely indicates that you have set the transfer point from first-stage to second-stage injection incorrectly. Further, if you are molding the same part in both an electric press and a hydraulic press, you need to check out both. You may be surprised at the difference between them.

You might have a few molds that require a full shot at the end of first-stage injection, but that should be rare. Extremely small or micro-molded parts are exceptions to the rule, but that is because they are so small that it is impossible to use a typical two-stage molding process. (Yes, you can still practice Scientific Molding and use only one stage. But that’s another topic.)

There is a preferred method for troubleshooting: Take the hold pressure down to a low level, perhaps 5 to 25 psi on a hydraulic press; and for an electric press set pressure as low as it will allow or 100 to 250 psi plastic pressure. It is important to leave a minimum of 0.3 sec on the second-stage or pack/hold timer. Why? Refer to the previous experiment. It should show you that the part made with time on the second-stage timer is larger than the others. This means you get the see the machine’s response on switchover and the momentum involved in transferring from first to second stage. Another way of stating this is that we get to see what happens during transfer if you do have second stage on. Most jobs run with some time on the hold timer and you need to understand the over-travel that often occurs in the first stage.

To illustrate the value of taking hold pressure off to obtain information about a part problem, let’s use an example from our list. Let’s say you have a part that is flashing, either sometimes or all the time. Most troubleshooting guides suggest reducing injection pressure. Sorry, this is simply wrong! With Scientific Molding you must have an appropriate Delta P on the first stage, so reducing first-stage pressure is not an option.

In troubleshooting flash, the first question is: Is it occurring in the first or second stage? How do you tell? Taking off the second stage via by eliminating time on the second-stage timer may not provide an answer, because you will not see the overtravel after the first stage. Note in the first experiment described above that the part with time on the timer is larger than the others. However, taking the hold pressure down to a low value and leaving some time on the second-stage timer will tell you what you want to know: Is it the first or second stage that is causing flash?

Ram overtravel could be causing the flash. If you see flash and the part is filled and packed with second-stage pressure set low, you are going in too far in the first stage. You need to re-establish your stroke transfer position to fill less material during the first stage of injection.

If you have a short shot by volume and there is flash, you have a parting-line or clamp problem—in other words, a tooling or press problem—but not a processing problem. There is very little pressure on the parting line when the part is short by volume. You cannot build much pressure on the parting line until the part is completely full for most parts. Thin-wall molding can be an exception.

If the part is about 90% full, with no flash, by ending the first stage on position with low second-stage pressure and some time on the second-stage timer, the problem causing flash during molding is too much pressure in the second stage, or you have a weak parting line. Try reducing second-stage pressure.

If this does not resolve the flash, get the parting line checked out, and do not be fooled by using bluing compound. A good parting line needs 3000 to 7000 psi to hold. Bluing will transfer from one side to the other with just 5 lb of touch force.

What’s more, the parting-line test has to be done with the mold mounted in a press, because molds flex with the platens. This phenomenon will not show up in a spotting press.

Related Content

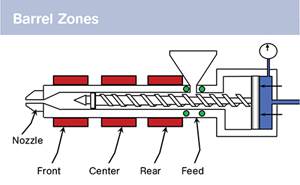

How to Set Barrel Zone Temps in Injection Molding

Start by picking a target melt temperature, and double-check data sheets for the resin supplier’s recommendations. Now for the rest...

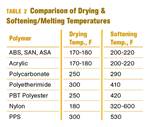

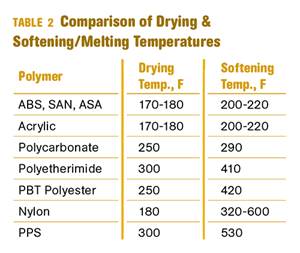

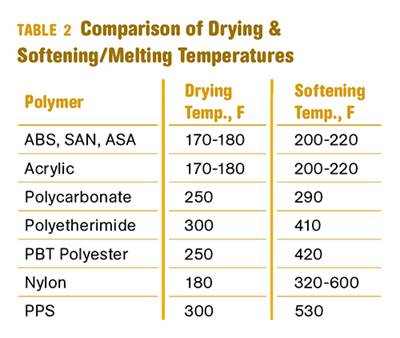

Read MoreWhy (and What) You Need to Dry

Other than polyolefins, almost every other polymer exhibits some level of polarity and therefore can absorb a certain amount of moisture from the atmosphere. Here’s a look at some of these materials, and what needs to be done to dry them.

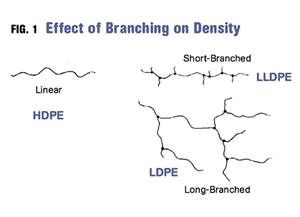

Read MoreDensity & Molecular Weight in Polyethylene

This so-called 'commodity' material is actually quite complex, making selecting the right type a challenge.

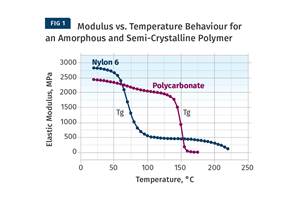

Read MoreThe Effects of Temperature

The polymers we work with follow the same principles as the body: the hotter the environment becomes, the less performance we can expect.

Read MoreRead Next

Why (and What) You Need to Dry

Other than polyolefins, almost every other polymer exhibits some level of polarity and therefore can absorb a certain amount of moisture from the atmosphere. Here’s a look at some of these materials, and what needs to be done to dry them.

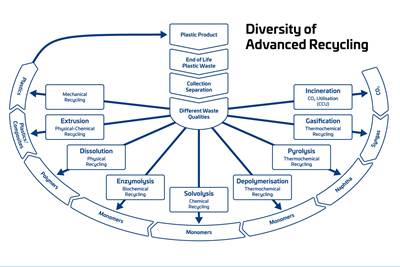

Read MoreAdvanced Recycling: Beyond Pyrolysis

Consumer-product brand owners increasingly see advanced chemical recycling as a necessary complement to mechanical recycling if they are to meet ambitious goals for a circular economy in the next decade. Dozens of technology providers are developing new technologies to overcome the limitations of existing pyrolysis methods and to commercialize various alternative approaches to chemical recycling of plastics.

Read More.jpg;width=70;height=70;mode=crop)