Injection Molding: Processors: Teach Part Designers The Golden Rule

Make sure the designers you work with understand that there are limits to what processing can do.

Make sure the designers you work with understand that there are limits to what processing can do. Last month, three different clients hit me with basically the same problem: We are having difficulties molding our customers’ parts and are getting greater than 20% rejects. The parts have non-uniform walls, ranging from 0.050 in. to 0.240 in., are made out of a semi-crystalline (high-shrink) resin, and have to be cosmetically perfect.

I almost flew into a rage. Molders cannot beat Mother Nature… she wins all the time. We cannot violate laws of physics, specifically heat transfer. Plastic parts shrink as they cool. Period.

Remember the Five Key Components to molding a successful part, as defined by my colleagues Glenn Beall and Mike Sepe:

- Part design;

- Material selection and handling;

- Mold/tool design and construction;

- Processing;

- Testing.

Put them into practice and you will make parts faster, with high quality and less hassle. And more profit.

But each of the five elements above has hundreds of details and they all interact. Like tires on a car, you need all of them to work together to get anywhere. It is a complex situation, but the frustrating part is that it seems we do not want to use the basics that were taught 50 years ago: In plastic part design, the first and golden rule is uniform nominal wall. Here’s why.

First, understand that molding parts from plastic pellets is a thermal process. We must heat the granules to melt them, then form the part and cool the plastic so that it solidifies and holds the shape of the cavity. Let’s focus on cooling a plastic part in the cavity. Plastics shrink upon cooling. A thicker section of a part will stay hot longer and shrink more than a thinner section.

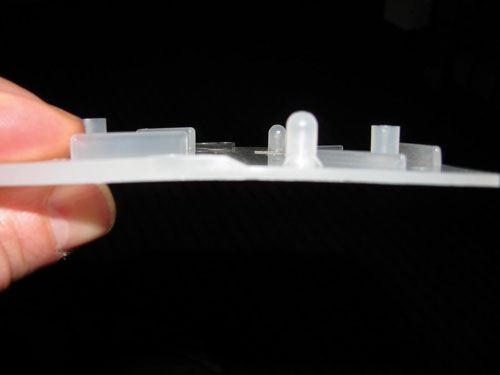

Figure 1 shows a sample block Glenn Beall designed to demonstrate more than 30 common problems in part and tool design, processing, and plastic response to processing. Note that one side of the block is significantly thicker than the other, roughly 0.150 in. vs. 0.075 in. The thick section cools more slowly and shrinks more than the thin section, pulling the thin side down and warping the part. This is with a high-shrink, unfilled, semi-crystalline resin such as polypropylene, polyethylene, or acetal. The warpage would be less with a low-shrink amorphous polymer such as ABS, HIPS, or polycarbonate. The amount of shrinkage is polymer-dependent and proves the need for different rules for allowable nominal-wall variations in different polymers.

Infrared (IR) thermal imaging has great potential as a troubleshooting and inspection tool in plastic processing. In this issue of thick vs. thin nominal wall for part design, IR provides some amazing data. Figure 2 shows the thermal image of “Beall’s Block” about 15 sec after ejection. Note the difference in temperature between the thick section at 238 F and the thin section at 118 F. This picture screams at us to pay attention to keeping the nominal wall uniform. It also clearly demands that the customer pay more for that part. If the part has thick sections, it has to stay in the mold longer to cool, hence there is more machine time—and extra plastic—that have to be paid for.

How can any sane toolmaker, designer, processor, manager, or executive see this picture and expect a flat part? Any attempt to prevent this part from warping with a high-shrink resin would be fighting Mother Nature, and she will beat you every time. The thick section will stay hot longer no matter what the mold is made of or where the cooling lines are. You can try to fixture the part to prevent or minimize warpage. But as Mike Sepe would say, such an approach makes for unhappy molecules, and if you put the part through a thermal cycle or two, it will warp.

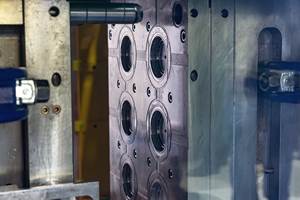

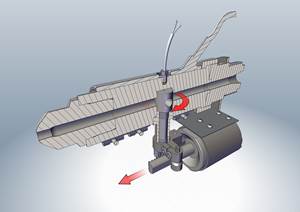

This principle can also be translated into tool design. You may have a uniform nominal wall, but if the cooling lines are not properly located you will have differential cooling, resulting in differential shrinkage. Not an easy problem to solve when you have cores forming a barrel or well in your part. It is easy enough to get cooling lines spaced evenly in the cavity, but cooling the core is often difficult and costly. And in most cases the plastic shrinks onto the core and away from the cavity. Thus, the core has to take out more heat. Pay to have the tool built properly.

Make this your molding mantra: All five key components listed above interact. Design must provide a reasonable nominal wall. Different resins have different shrinkage characteristics. Tool design and construction must provide proper and uniform cooling. Processing must properly pack out the part so the part stays in contact with the mold surfaces. And testing must check the part to make sure it will not distort in the application or in shipping.

Folks, let’s get our act together.

About theAuthor

John Bozzelli is the founder of Injection Molding Solutions (Scientific Molding) in Midland, Mich., a provider of training and consulting services to injection molders, including LIMS, and other specialties. E-mail john@scientificmolding.com or visit scientificmolding.com.

Related Content

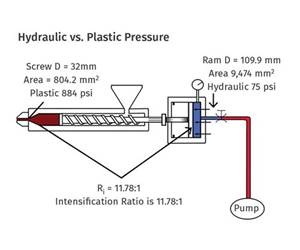

A Simpler Way to Calculate Shot Size vs. Barrel Capacity

Let’s take another look at this seemingly dull but oh-so-crucial topic.

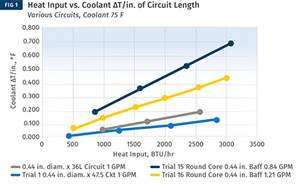

Read MoreImprove The Cooling Performance Of Your Molds

Need to figure out your mold-cooling energy requirements for the various polymers you run? What about sizing cooling circuits so they provide adequate cooling capacity? Learn the tricks of the trade here.

Read MoreKnow Your Options in Injection Machine Nozzles

Improvements in nozzle design in recent years overcome some of the limitations of previous filter, mixing, and shut-off nozzles.

Read MoreRead Next

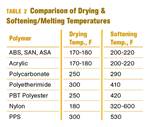

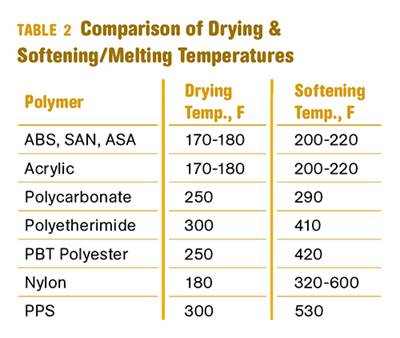

Why (and What) You Need to Dry

Other than polyolefins, almost every other polymer exhibits some level of polarity and therefore can absorb a certain amount of moisture from the atmosphere. Here’s a look at some of these materials, and what needs to be done to dry them.

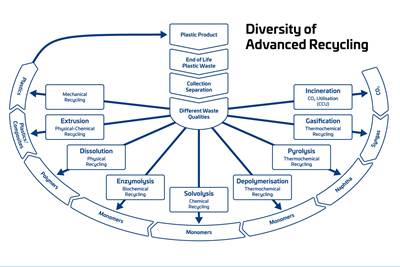

Read MoreAdvanced Recycling: Beyond Pyrolysis

Consumer-product brand owners increasingly see advanced chemical recycling as a necessary complement to mechanical recycling if they are to meet ambitious goals for a circular economy in the next decade. Dozens of technology providers are developing new technologies to overcome the limitations of existing pyrolysis methods and to commercialize various alternative approaches to chemical recycling of plastics.

Read MoreHow Polymer Melts in Single-Screw Extruders

Understanding how polymer melts in a single-screw extruder could help you optimize your screw design to eliminate defect-causing solid polymer fragments.

Read More.jpg;width=70;height=70;mode=crop)